Why would anyone consciously decide to implement a technique with a name that starts with the words “management intensive?” Management Intensive Rotational Grazing attempts to mimic the natural movement of ruminants - those animals uniquely equipped to digest hay and grasses - as they are influenced by seasons, predators and scarcity or abundance of food. Though it seems counterintuitive, problems of overgrazing often have less to do with too many animals on not enough land and more with the removal of natural motivators that keep them moving. The “management intensive” part comes from watching the progress of the animals on a particular section of pasture and moving them to fresh grass when the time is right. “Rotational” means that they might not set foot on the same ground for 6 months or a year, giving the grass a chance to recover and minimizing the chances of picking up parasites.

Take our four acres in Petaluma, maybe two and a half of which are grazeable pasture on which our sheep are allowed to roam freely. While we should have plenty of forage for our small herd of 6 Blackbellies and 2 Suffolks, around this time of year (the middle of the summer), we find that our lower pasture of about half an acre has been scoured down to bare dirt while the upper pasture has become overgrown. To make matters worse, the overgrown areas develop aggressive populations of invasive thistles which, if allowed to flower, will release thousands of tiny seedpod paratroopers to colonize more territory each year.

The problem, as I understand it, lies in ice cream. No, not literal ice cream but any food one might prefer to eat without any motivation not to. In this case, the ice cream is the delicate new growth on a recently munched tuft of grass or a particular variety of grass they really like; This is ruminant desert, although the sheep won’t get fat from it. In fact, by repeatedly returning to the same specific grass plant to nip off each new sprout, they are discouraging the establishment of deeper roots – think of the plant trying to mirror what grows below ground with what it has above – and giving fast-growing weeds the advantage in the competition for water, sun and nutrients. While this particular “ice cream” is actually high in protein, it does not contain the quantity of dietary fiber the animals need to thrive. Ironically, away from the sundae bar, the rest of the grass – the healthy stuff – is growing past its prime and becoming excessively fibrous and harder to digest.

This year was our first Spring with the sheep, and just when we thought the grass was growing at its best and they should have plenty to eat, we started to see pronounced hip bones poking through the hides of the Blackbellies. They were losing weight and suffering from “scour” – a wet mucousy diarrhea (but let’s just call it “scour” from now on) – caused by the high protein/low fiber diet. Continuing with the delightful farmy imagery, one particular wether was showing the preliminary signs of a rectal prolapse. Yep, it’s lovely, but he’d been pushing so hard he was starting to turn inside out. Preliminary consultations with Dr. Google DVM indicated that the typical treatment either involved a tourniquet in the form of a tight rubber band on the exposed tissue or mint jelly and a side of rosemary potatoes.

In a factory environment, producers would resort to feeding grain to fatten their animals back up. Because the rumens of sheep are not designed digest grain, this process can release excessive lactic acid and drop the pH in their digestive system. It’s commonly thought that in this environment bacteria such as the E. coli O157:H7 typically responsible for meat recalls can develop, although there has been some backlash of late against this theory (and now I just came across some backlash to the backlash that makes for interesting discussion).

In any case, trying to feed our sheep grain has not always worked out perfectly. In an effort to make sure everyone would get a little and no one got too much (the big sheep bullying the little ones), we tried hanging 5 buckets a few feet apart along the fence. We’d then put a little grain in each bucket and watch as they all bobbed from one to the next making sure they hadn’t missed any. Unfortunately, one bucket wasn’t wired to the fence quite securely enough and, in the scuffle for the last morsels, unhooked from the fence with the handle around the neck of one of the Blackbellies, the male with the prolapse. Each time he tried to shake it off, it made a huge commotion causing the rest of the sheep to run. He’d then follow them – as sheep will do – making even more noise and causing them to run faster.

To make matters worse, I started chasing “Buckethead” which kept the cycle going. I felt like I was in a whirlpool as the seven of them went round and round with the eighth trailing along behind. “Hey guys, wait for me! Something weird is chasing me!!” Mind you this was at about 6 am. I had woken up early for no reason and just casually walked out to the pasture to give them a little snack. I just knew Ann would look out the window in the baby’s room any second wondering what the racket was and see me playing hide and seek around the water tank with a sheep with a bucket on its head. I suspect she’d just go back to bed. On a side note, when I finally did tackle the wether and remove the bucket, I noticed while he was scampering away from me that the prolapse had receded from all the activity! Guess we’re having pork tonight.

And besides, we’re not only interested in feeding the sheep on grass alone for their health but also for the health of our pastures. Grazing is a natural and helpful process for grasslands; It thins overgrowth, distributes organic material and spreads the seeds of native perennial grasses. On a Saturday afternoon, I went out to Tara Firma Farms just outside of town for a talk on pasture management. Their 300 acre property has seen many of the same problems we’re having on our little farmlet, but through 3 years of diversified farming and Management Intensive Rotational Grazing, they have seen a dramatic improvement in the quality of their pastures and a return of perennials. I left the farm sneezing my nose off but with a new commitment to implementing a rotational grazing strategy on our property.

I walked outside with the iPad and pulled up Google Maps. A blue dot showed my current location just west of the main road within a thin brown line showing the property border on a yellow background. With a click in the lower right corner of the screen, the map peeled back so I could select the satellite view. A green landscape dotted with trees appeared square by square. I could pick out the long narrow galvanized rooves of the two old chicken houses at the back of our property, pasture around them, the lower pasture just west of the house and my position towards the back of the sun garden. I simultaneously clicked the menu and power buttons on the iPad to send a screenshot to my photo roll. In the SketchBook app, I imported the image and began to divide up the property.

This was not the first time I had decided to try to rotate the animals on the property. Reading “Omnivore's Dilemma” led us to Joel Salatin which led us to a book called “The Accidental Farmers” and a mild obsession with the authors’ “Natures Harmony Farmcast” (now the Farm Dreams Farmcast) while driving through Central America. The podcast was sponsored by Kencove Fencing and some deeply embedded marketing trigger resulted in me ordering four 164’ rolls of Kencove electric mesh fencing and two charge controllers soon after we closed on the house.

The challenge this time was minimizing the “management intensive” part, so I went about figuring out how each of the divisions could be created 1) with less than three segments of fence (I need one for a pig enclosure if we raise another couple feeders) and 2) so only one section needed to be moved to create the next area.

The sheep reluctantly followed me (or more accurately, the tupperware of grain I was carrying) up to the first enclosure and looked insulted when I pulled the fence across behind them. Then, one by one, they dropped their heads and took a cautious bite of the knee high grass. “Wow! This stuff is great! Why you been hiding this from us? You know that lower pasture is pretty much barren, right?” Yeah, I know, genuises.

In addition to a “learning curve” in setting up and tearing down the electric mesh fences…

… the other reason the previous attempts at rotational grazing had failed was concern about predators with the animals so far away from the house where we couldn’t see them. You may remember that we had one sheep attacked by something back in the Spring and had heard stories of the previous owner losing even big Suffolks to a predator. We’d pretty much decided that a llama, considefred great guardian animals because of their instinct to stand their ground rather than running, was the answer. With the Sonoma=Marin Fair a few weeks away, we figured we’d go down and try to pick up 4th place ribbon winner from a 4H’er on the cheap. Still, we expected to pay around $1000 for a llama.

Then one popped up on CraigsList for $75. A family way back up in the hills of Penngrove was moving down into a small condo in town and couldn’t keep her. They’d gotten her a few years ago after losing several lambs to a coyote and hadn’t had a problem since. The woman was quite attached to her and just wanted to see her go to a good home. When our little family showed up with a bright eyed baby in tow and talk of a farm with sheep, she practically begged us to take her.

A quick call to the neighbor above us and he generously offered to let one of his employees who had a horse trailer pick her up for us while on the clock. Country folks! She wasn’t quite sure of her fate when we opened the trailer door at our place and no amount of shoving or bribing was going to get her 300+ pound frame to move. Finally, when we backed the trailer up to the open pasture gate, she decided that looked better than the hard floor and got up, making it clear this was her choice, not ours.

Though the sheep were quite interested in this new arrival, the llama was going to keep the welcoming party at a distance.

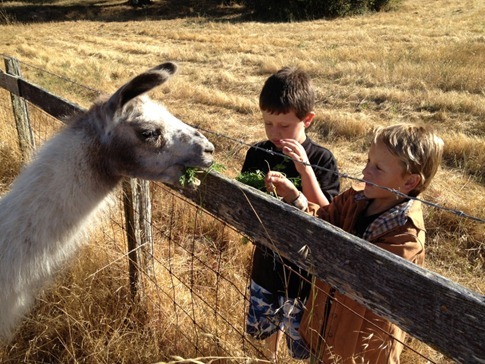

But within a week or so, she warmed up enough to accept some extra carrots from the garden from the neighbor’s kids and is now happy to bury her head up to the floppy ears in a bucket of grain from either of me or Ann.

While we hope she’ll continue to bond with the rest of the herd and possibly one day convince a coyote to go in search of easier prey, we feel a little more comfortable with her up there and are growing to love her. With the knowledge that she’ll never end up in the freezer, we’ve given her a name. Meet Michelle… Michelle Ob’llama.

As a great bonus, we’ve recently discovered that our llama has a distinct similarity with her namesake in The White House; They are both great supporters of gardening, although I should mention that only the camelid does it with her manure. In fact, not only is llama manure (“llamanure”) considered one of the best fertilizers because it can be used fresh from the… uh… source… without burning plants, but they tend to go in the same place every time, making collection easy.

Livin’ the dream.