We’ve been on our four acres an hour north of San Francisco for just over a year now and are starting to feel the rhythm of the place. We’re not surprised when the chill of fog spills over the hills from the Pacific Ocean thirty miles to the West at the end of a 90 degree summer day. We know the giant buckeye tree supporting the tree house built by the previous owners for their grandkids will be the first to show its leaves in the Spring and the first to lose them in the Fall. We know that a single zucchini plant in the garden can produce enough vegetable matter to feed a village, that if left unchecked will grow gourds the size of a speed skater’s thigh and that every neighbor within 10 miles has the same problem and does *not* need a loaf of Ann’s signature zucchini bread.

We’ve started to get a sixth sense when looking out towards the pasture from our long farm table in the kitchen. In addition to telling the time of day by how far Petunia, the 8 year-old Vietnamese Potbellied Pig who has been a long term resident of the property, needs to walk from her nest of straw to find a swath of sunlight to warm her leathery skin, we can tell when something is not quite right. We’ll look up just as one of the sheep bolts across our view and watch closely for anything with four legs, teeth and claws that might be pursuing it. We’ll notice the black and white cat, born to a feral mother under a pallet leaning against an old chicken house in the back of the property, slinking mischievously along the fence line with one eye on our big Rhode Island Red while her head is down pecking and scratching at the dirt.

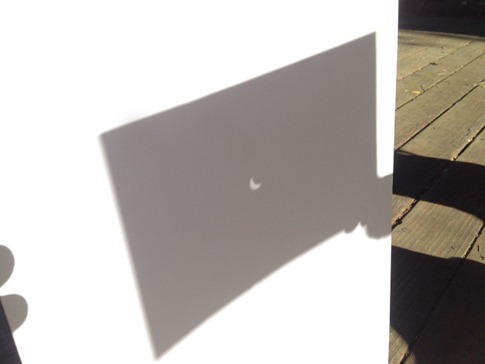

The evening of May 20th, 2012 seemed to come early, the day not fading so much as the dusk sneaking in. A weight was in the air, an ominous feeling that told us something was different. While the shadows grew long in the pasture, the remaining rays of sunlight had a distinct precision. A pull could be felt from the west, and we were drawn outside onto the deck like zombies, eyes trying to make sense of the changing light. While Ann held the baby close, I found two pieces of white cardboard and poked a hole in one. The pinpoint of light projected onto the blank canvas showed the beginning of the eclipse, the moon sliding between the sun and the Earth.

We’d become so sensitive to the patterns of the sun since moving to the country. Knowing where and when it would shine was essential for laying out a garden, providing shade to the animals, keeping the house cool and avoiding the heat of the afternoon for the hardest farm chores. And when the sun would set, an impermeable black, unspoiled by the light pollution of the city, would lay heavy like a blanket. With the darkness came the unknown. Plants wouldn’t grow and animals huddled together for warmth and waited for the relative security of the day. Watching the premature nightfall on the pasture, it was easy to imagine the uncertainty people living before we had knowledge of the planets and their orbits must have felt. Even with access to 24 hour news and the Internet, it was hard not to feel pretty insignificant as something 2,000 miles across and 200,000 miles away begins to obscure our sun.

As the eclipse progressed, each surviving ray of sunlight began to mimic the crescent shape projected on our makeshift viewer. Soon, we were surrounded by tiny half moons filtered through the trees.

I expected the animals to react more dramatically to the changing light, but they turned towards it and awaited their fate with the rest of us.

A few weeks later more unusual shadows darkened the pasture, and again, brought with them an uneasy feeling. Ann was home alone with the baby while I was out all day. She’d just called after lunch to check in when she saw them, dark swatches slashing across the grass. At first, it looked like a low flying plane momentarily obscuring the sun. After all, Liberty Field, a dirt landing strip nestled between cow pastures and strawberry patches, was located just a few miles east, and we often waved to small aircraft as they passed overhead while we were working in the garden. But these were circling. Then, just on the other side of the fence, Ann noticed what looked like a turkey. Then another, and another.

Suddenly two dark figures took up posts in the trees, passing solemn judgment on the scene below. Those were not dopey turkeys, wandering around mindlessly waiting to become Thanksgiving dinner; Those were vultures, and they were the ones settling into a meal. Where there are vultures, there’s death, and as Ann walked out towards the small gate at the end of the lawn that leads into the pasture, she saw the explosion of white feathers and began to fear the worst.

We’d lost chickens before, most recently after being gone for two weeks on the other side of the world. We’re new to the farm life and still working to find a balance between our desire to let our animals roam free and the need to keep them confined for their safety. We’d decided that just because we would be gone, there was no reason to alter the schedule for our nine chickens. The automatic door on the coop would still open on a timer in the morning allowing them to roam our 4 acres and close securely at night after they’d reliably returned to their roosts just before sunset. We didn’t count on a historic electrical storm hitting the Bay Area that would knock out power and skew the timing on the door; They were caught outside one night and killed by an opportunistic passing predator. Well, all but two were killed. One, a Rhode Island Red who had taken to escaping from the pasture and roosting in the feed shed, remained, as did an Ameracauna who had decided to set on the nest in an effort to hatch several (unfertilized) eggs the flock had laid in the previous days. That was the last time we’d seen vultures in the pasture.

But out of the dark had come light, from tragedy had come hope, hope in the form of eight fertilized eggs we’d procured from a nearby farm for our insistent mother to set on. For twenty and a half days, she diligently rotated the eggs and kept them warm until on Mother’s Day, the tiny, wet balls of fluff emerged from their shells.

As Ann approached the pasture gate, it was clear that the meal the vultures were enjoying was our faithful mother hen. And the chicks? Ann looked left to find the egg collection door, just inside of which the vulnerable chicks would have been nestling in a bed of hay, wide open. Inside, she was crushed to find that they had met the same fate as their mother.

As we tried to reconstruct what had gone wrong – Which one of us had left the egg door unlatched? What could have jumped or climbed 5 feet up to it? Had the mother left the coop in an effort to lure the attacker away from the chicks? – the Rhode Island Red came strolling up like that one character in a movie who’s timing is always just a little off? “Hey guys, what’d I miss?” Putting aside for one second the theory that she’s been the one decimating our flocks the whole time and then playing innocent, she must have once again been off exploring the far reaches of the property or hanging out in the feed shed.

For many, the idea of “returning to the land,” providing their own food and restoring a link to nature is an idyllic notion. But along with new found awareness of the cycles of light and dark from the sun comes a connection to a deeper cycle of life and death on the farm. For some of the animals we raise, there comes a day when all of the life they experience is converted into sustenance for our own lives, and for the chickens we’ve lost, sustenance for a fox or a coyote or a raccoon or a skunk – or even an innocent looking red chicken. We’ve come to understand that there’s an emotional toll for lifting the veil on the source of our meat or eggs, but when presented with the options of CAFO’s and overcrowded and unsanitary chicken houses, we’re willing to pay it.

As the satiated vultures beat their huge black wings back into the air, off to cast their shadows on another pasture, there was a flash in the coop, a white gray streak low along the mesh wall; It was one of the chicks, bobbing a weaving like she was still evading pursuit. She had survived, likely by using the same tactics that eventually caused me to give up on catching her and putting her in a cardboard box under a heat lamp each night. Like her mother – and that unkillable Rhode Island Red – she’d beaten the odds and given us glimpse of the light in a time of darkness.

The next day, we went down to the feed store in town and picked up 6 more chicks: 2 Golden Laced Wyandottes, 2 New Hampshire Reds (we’ve had good luck with red chickens from the northeastern states…), and 2 Delaware Whites. I’ll add a spring to pull the egg door closed and a better latch to secure it tightly, and we’ll enjoy these chicks and the eggs they’ll start laying in a few months while we have them.

Everything’s back to normal on the farm for now, but we can’t help but keep one eye on the pasture, watching for shadows.