I’ve always assumed that when the baby came, we’d be running around the house frantically stuffing things into a suitcase. I’d get out to the car with the bag only to realize I’d left Ann sitting on the couch doing comical deep breathing exercises. She’d give me one of those looks, and I’d help her out the door where her water would break on the curb beside the mailbox. We’d race to the hospital, me with my head out the window making “wee-woo” siren sounds and Ann in the backseat yelling “We’re not gonna make it! She’s coming NOW!”

I know now that pretty much only happens on sitcoms. Instead, we scheduled the induction for a Tuesday morning, the end of Ann’s 39th week of pregnancy. Our OB felt that with Ann’s blood pressure running a little high, there was no sense risking any additional stress on the baby as its lungs would have been fully developed as of the 36th week. We considered that if the baby were to decide to come two weeks late - not uncommon for a first child - Ann would be looking at 3 more weeks of a sore back, peeing every 3 minutes and not being able to see her feet, and I’d have to continue to wait to meet the little creature who’d been living in her belly. Really, it came down to what our doctor thought was best for the baby. So instead of the “wee woo” scenario, we double checked a list of things that friends and family had told us we’d want at the hospital, set the automatic chicken door and pig feeder, and calmly walked out the door for the 7 minute drive we’d been thinking about for 9 months, this time with an empty infant car seat in the back.

We’d been warned by my brother, a doctor, that not much would happen in the first day of being at the hospital so had basically prepared reading materials and digital content as if we would be trapped on a 14 hour plane ride to New Zealand. Instead of beer, wine and a selection of liquors, Ann was given an IV cocktail that, while originally used in the treatment of ulcers, had been shown to bring on the first stages of labor. And sure enough, just about the time we would have touched down in Christchurch, Ann told me that she’d been having increasingly intense contractions for an hour or so. Nonetheless, I needed facts and referred to the ticker tape creeping out of a machine beside the bed with wires running to sensors stuck on her belly. Since we arrived, the needles on the machine had traced out both the ups and downs of the baby’s heart rate and measured tightening of Ann’s abdominal muscles that would indicate a contraction. The dispersed, sloped foothills that I’d been watching all day on the tape – the nurses had been telling Ann she had a “spastic uterus” – had in fact become Southwestern buttes with steep rises and flat peaks. I was happy to be able to confirm for Ann that, based on my analysis, she was indeed feeling pain. Her response was mumbled, but I think she might have said “Good luck yourself.”

Through the night, everything progressed perfectly with her water (the doctors and I insist on referring to it as her “bag of water,” and while they do it because it’s technical , I do it because it makes her cringe) breaking naturally and contractions continuing. By morning, the second “induction concoction” including Pitocin was started by IV and the pain was increasing right on schedule (according to the machine by the bed ;~) ). Since we arrived, we’d been hearing the escalating cries of women in the adjacent rooms as they progressed from about this point. I don’t even want to attempt to describe the pain, fear, surprise and determination I detected in each half moan/half scream until finally, all would be quiet and we’d hear the faint cry of a newborn. This preview, despite the happy ending, did little to comfort Ann nor did a new nurse walking in every couple hours to quip, “There’s a reason they call it ‘labor.’” Interestingly, they’d also roll their eyes a bit with each scream, muttering something like “Enough already, just get the epidural!” and then to us, “About 2/3 of women who come in swearing they want to do it naturally, end up getting one.”

And that had been Ann’s plan all along. We’d been told by enough friends who had them that the sensation was still there, without the pain, and by enough doctors that there were no side effects, so it seemed like a no brainer; Not getting one seemed akin to trying to get a root canal without Novocain. Of course, to each their own, but seeing the relief on Ann’s face once the epidural was administered made me feel like it was the right decision. Ann’s subsequent campaign to name our daughter after the anesthesiologist – her name was “Misty” – made me question it.

The next exams showed enough progress that our usually cautious and conservative OB starting talking about a delivery soon after sunset. Ann’s mom had just landed at San Francisco airport and was driving north with my mom and would arrive at the perfect time. Everything was coming together. Unfortunately, that’s where the momentum stalled, and as they got closer, we had to tell them that the next few exams found us right where we’d been in the afternoon. A few hours later, there was still no more progress. We'd been told that induction had about a 50% success rate and that a c-section was a real possibility. Again, we’d gone forward, feeling that we wanted to do whatever was best for the baby’s health.

At around 10 pm on Wednesday, 39 hours after we’d arrived at the hospital, we agreed with our OB that it was time to throw in the towel. Our other option would have been to dial back the strength of the epidural so Ann could painfully grunt around on all fours in the hopes of the baby adjusting into a better position sometime over the course of the next 4 to 18 hours. The prospect of having the baby out and with us in about an hour sounded pretty good by comparison. I put in a quick call to my brother to run the decision by him. He agreed that it sounded like the right medical course of action but added that my sister-in-law Meghan had something to share from her experience; She insisted that I warn Ann that the table in the operating room is really narrow and that it can feel like you’re going to fall off. So there I am the phone, having been handed a set of scrubs – hair net, one-piece jump suit, and shoe covers – and with a nurse looking at me, tapping her foot impatiently. I said, “Okay. Tell Meghan I’ll Ann about ‘the skinny table.’” As they wheeled her towards the operating room, Ann, also dressed in her hairnet and fully prepped for surgery, said “What’s ‘the skinny table?’ Did Meghan say I should have them do a ‘tummy tuck’ while they’re in there?”

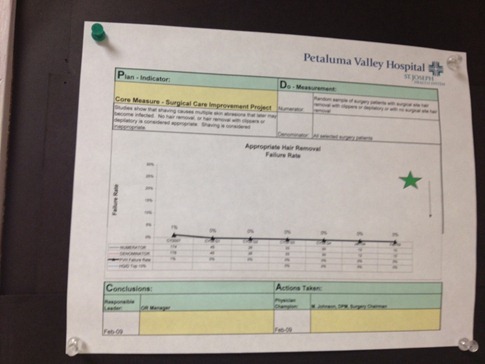

They made me wait outside for a few minutes while they got her draped and set up the operating room. Browsing the surgical ward’s bulletin board, I was reassured to see that their “Appropriate Hair Removal Failure Rate” had been low and level for the previous months.

For being in a sterile room with 8 strangers and only a thin blue drape to separate us from Ann’s fileted abdomen, the experience in the operating room was a lot less scary than we’d imagined. The surgeons and nurses counted every tool – both before opening and after closing – and Ann’s favorite anesthesiologist (maybe “Misty” would be a good middle name?) stood right beside us making sure she was comfortable. At one point, our masked OB peeked over the drape to tell us that the baby was "sunny side up" - nose facing Ann's belly button rather than her spine - and wearing the cord like a belt around her waist. She likely would never have moved down to a point where labor could have progressed naturally.

For the past month, we’d been getting regular ultrasounds and had seen the baby’s little chest rising and falling. “She’s practicing breathing,” the tech would say. Practicing because she was really taking amniotic fluid into her lungs rather than air; The oxygen she needed was being supplied via blood through the umbilical cord. But during birth, this system somehow knows to switch over. Once fluid is expelled from the lungs, either when traveling through the constriction of the birth canal or in our case via suction in the operating room, oxygen can be absorbed directly into the previously waterlogged lungs. That first gasp of breath or cry signals that the new system is online and the old one, the umbilical cord, can be severed.

At 10:20 pm on Wednesday 1/4/2012, the creature that had been growing inside Ann for 9 months, flicking her bladder and poking her elbows against the inside of her belly, took her first breath and let out a healthy cry. After some quick cleanup, the doctors wrapped her up and brought her over to us on the other side of the curtain. It’s absolutely bizarre to look at a completely little human that our two bodies somehow (I’ll tell you when you’re older) created.

She weighed in at 7 lbs 2 oz. Skin color? Wrinkly. Hands? Blue. Demeanor? Pissed.

Besides being a little groggy from the epidural and the Demoral – caffeine is considered a “hard drug” in Ann’s world – the new mom was feeling fine after the surgery. I went upstairs with the baby for about 20 minutes while they cleaned her up a little more and ran her through some routine swabs and pricks (Vitamin K and an Erythromycin ointment in the eyes, both of which we’d been asked about and advised were a good idea). After a little time in Recovery for Ann, we presented the baby to the grandma welcoming committee anxiously waiting back in our room. We also got a chance to announce her name to them, a secret we’d kept for 9 months; Wynne Marilyn Zimmerman was named for my mom’s father and her brother, Winthrop and Win Jr. Long, and Ann’s mom’s mother, Marilyn Wilson.