Wenceslao Monroy had explained the name “CHePe” by drawing in the dirt with a stick. First he scratched out a dusty “CH” and said “Chihuahua.” Next to it, he drew a “P” and said “Pacifico.” Then he carefully added the two lower case “e’s” and pronounced the whole whole word, “cheh-peh.” The CHepe is the train line that runs from Chihuahua in the Sierra Madres to Los Mochis on the Pacific Coast. Excited by the opportunities for cross cultural exchange, I wiped away the “e’s,” replaced them with an “i” and an “s” and pretended to ride on a Highway Patrol motorcycle with a tight shirt on.

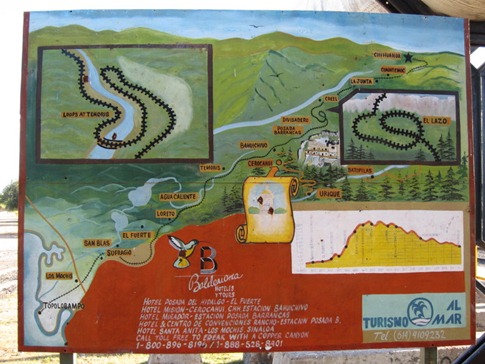

The CHePe line was completed in 1961 after almost a century of construction. After traveling about three quarters of its 653km, 37 bridges and 86 tunnels, you can start to see why it took so long. Today it functions as a major connection between the inland the coast and is the only passenger train in regular operation in Mexico. But the main reason that tourists ride the train is to access the spectacular Copper Canyon, Barranca del Cobre, really a series of 20 deep valleys covering an area four times the size of the Grand Canyon.

As the train approaches the station, you can hear the whistle blow as it clears a few intersections before the landing. Even as the brakes are still squealing, the conductor, sharply dressed in a black suit and vest with forest green accents either on a hat or pocket square, is down the stairs and reaching for your ticket. The clientele, at least on the Primera Express train which bypasses local stops and arrives in Chihuahua a good five hours before the Clase Economica, is a mix of tourists and well-heeled Mexican travelers. Once aboard, a second conductor (semi-conductor?) asks how far you’ll be riding and directs you to a seat. He’ll make a note of your location and come by to tell you when your stop is approaching. Before you realize it, the train is back in motion and rolling slowly but steadily into the mountains.

If you’ve stayed in El Fuerte for the night, you’re spared the level two and a half hours from Los Mochis and quickly find the rails carving through increasingly dramatic canyons. First timers set up camp in one of the doorways between the cars to take in unobstructed views of the high cliffs jutting through the thickening vegetation and with them, unfiltered lungsful of the black diesel smoke that flows out the stack of the locomotive and trickles down the back of the train. The rails begin to double back on themselves as they climb up out of the canyon. Pine trees take over for lush tropical cover and the landscape begins to look a lot like the foothills in California, with a few more catcti interspersed. Without knowing it, you’re riding along a high plateau with the expanse of the Barranca del Cobre opening up just out of sight.

We put together a little video to try to capture the experience…

At Posada Barrancas, we planned to find a place to stay near the canyons for a night. Well aware of the tourist bounty delivered each day at 1:40, three or four hotel and guest house shuttle vans were waiting as the train pulled in, and we disembarked amidst hawking from each of their drivers. Savvy travelers that we are, we confidently strode past them, immune to their tourist trap sales pitches. But as quickly as we entered the “town,” really just a collection of houses and a central “tiendita,” we were through it and coming to realize that those shuttles had been an extremely convenient offering which would have delivered us to the only services in the area. Not feeling quite so savvy, we trudged up the hill toward the main hotel with backpacks and bags hanging off both shoulders in the afternoon sun. By the time we dragged ourselves up to the reception, 30 minutes after the train had arrived and the first vanload of guests had checked in, the guy looked at us like “Where the hell did YOU come from?”

The Hotel Mirador was a splurge even after we talked them down $40 to around $200, but it included dinner and breakfast and, as we rationalized on the walk up from town, we came here to see the Copper Canyon and should really take advantage of it and stay right on the rim.

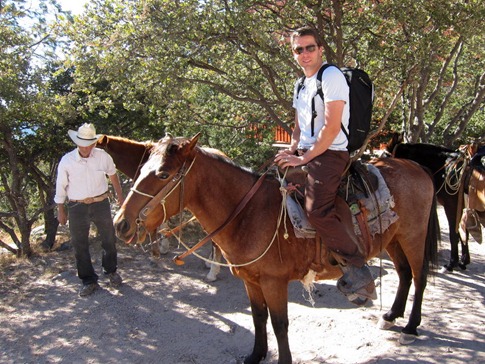

Having declined to dance the Macarena with the ten or so other hotel guests enjoying the very talented guitarist in the lobby the evening before, we were up early for a horseback ride to the teleferico, a brand new gondola descending into the canyons. Ann’s horse was named “Dola” or “Dollar,” but either way the similarity to the Spanish word “dolor” meaning “pain” could not be ignored. This particular steed seemed to favor a gait that offered a ride about as smooth as the Tacoma Narrows Bridge.

We'd opted to take the train rather than driving after hearing that remoteness of the region lent itself to marijuana growing and trafficking operations. We were shocked to learn that the brand new double cab Ford pickups we saw were not bought with revenues from the multicolor grass basket we bought for $2 from the five year old girl at the train station in Divisadero. And in hindsight, the canyon rim airstrip we rode along and the guards with machine guns who would fan out from the train each time we’d stop might have also been a clue. Still, we have yet to feel the least bit threated on the trip, in Copper Canyon or elsewhere.

Depending on who you believe, Raramuri, the name of Mexico’s largest population of indigenous people, means either “those who run fast” or “people of the good land.” If it’s the former, it refers to a time when they inhabited the fertile plains of Sinaloa before being forced to retreat into the rugged mountains by missionaries and expanding agricultural development. Today, estimates put the population at 50,000, some still living in ancestral cave dwellings and only about 40% with an outside source of income. Though some villages have embraced tourism, offering cultural tours, most Raramuri are skeptical of foreign visitors. Fortunately, the two girls and their mother, frozen in fear, suspicion and curiosity when we startled them in the woods collecting grasses for basket weaving, let down their guard when Ann’s horse farted violently, sending the girls into hysterics. Note to self: This may be a foundation for future cultural outreach.

Views of the canyons from the teleferico…

We were really stunned by the views in the bathroom…

We reboarded the train in the afternoon and spent a night in the tourist-focused, Western feeling town of Creel. It could have been the wind or the fact that we were there on a Sunday, but the streets were mostly deserted and gave us the feeling that the locals knew a Universal Studios style gun battle was about to break out.

We did have a good stay at the Plaza Mexicana which we’d recommend to anyone at 500 pesos ($37 or so).

By the next morning, we were ready to get back on the train for the seven hour return trip heading West. We found the truck right where we’d left it in the courtyard of the Hotel La Choza in El Fuerte, and after a dinner of the cauques, the local specialty of freshwater lobster (read: big crawdads) from the Rio Fuerte, we felt ready to get back on the road the next morning.